Processes of social exclusion act upon each other. For example, if you don’t have access to secure housing, you will find it much harder to access a range of financial services. In Britain, the 2007/08 financial crisis led to changes in legislation and budgetary constraints that increased tenants’ risk of eviction if they fell behind with their rent. In this research, we considered whether an initial £85,000 grant, made in 2010, from Lewisham local government to Lewisham-Plus Credit Union (LPCU) to fund immediate homeless prevention loans to members, helped to prevent social exclusion. These members were tenants at risk of eviction, who did not previously have a bank account.

Our results

The homeless prevention loans scheme is managed by LPCU. LPCU is a community savings and loan provider catering for people living or working in the south London boroughs of Lewisham and Bromley, as well as tenants of housing association partners in receipt of loans. Lewisham is in the top 20 per cent of most deprived local government authorities in England. In the recent past, Lewisham has been 12th in the UK for the number of homeless people, with more than two per cent of its population living either in temporary accommodation or sleeping rough. In 2010, around the start of central government’s austerity programme, Lewisham Council provided an initial grant of £85,000 for LPCU to provide interest-free loans to Lewisham tenants to clear rent arrears, and to prevent eviction and homelessness. The applicants did not need to have prior savings with LPCU. LPCU opened the credit union accounts through which the applicants repaid the loans.

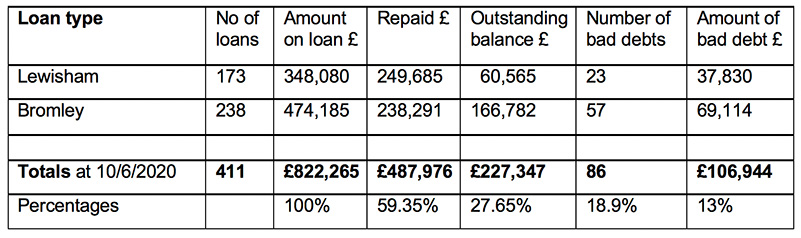

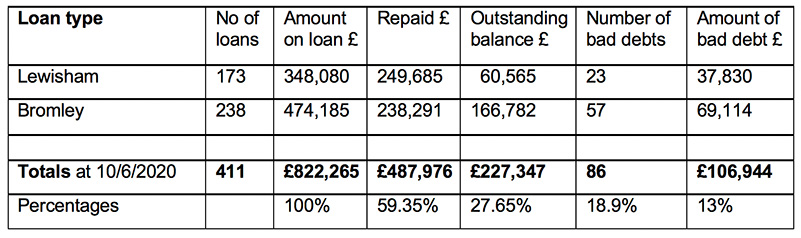

A number of tenants agreed that the repayment instalments would include a savings component. This meant that the loan recipients had a savings account opened for them. Tenants were able to access money paid into this account at the end of the loan repayment period. LPCU received an administrative fee for each homeless prevention loan. The scheme proved highly successful with all 411 loan recipients being saved from eviction. In addition, although the default rate is higher than that arising from LPCU’s loans to other members, the majority of recipients (85%) repaid their loans. The repayments provided the funds to extend the loans to others at risk of eviction. The scheme was extended to the neighbouring borough of Bromley. The number of people helped by the combined scheme up until June 2020 is shown in table 1 below.

Our research findings show that the scheme:

- Saved more than 400 families from eviction and homelessness

- Resulted in more than £800,000 being paid directly to social and private landlords’ accounts to repay rent arrears

- Created a virtuous cycle of multiplier effects so that repayments by one set of homeless prevention loan recipients were used to provide loans to other people at risk of homelessness on an ongoing basis

- Helped to develop good financial management practices among many who are most vulnerable to poverty

- Overcame the financial exclusion of many of the tenants by providing access to a savings account and loan facilities

- Increased membership numbers for the credit union

- Facilitated savings of more than £1million that the local government authority would have otherwise spent on providing advice, accommodation and other services to evicted families

- Provided an exemplary model for international bodies, central governments, local government authorities, other credit unions and all of those concerned with preventing homelessness and financial exclusion among the most vulnerable members of society.

Our research methods

The authors are a professor of accounting with an interest in credit unions and the services manager responsible for administration of the homeless prevention loans scheme at LPCU. The methodology was to build up a case study drawing on evidence from LPCU’s internal documents, observations and interviews, and informal discussions between the academic author and employees and directors of LPCU. The case study also draws on the practitioner author’s knowledge of homeless prevention loans. The authors analysed evidence using tabulated data about the loans prepared by the practitioner author. The authors identified patterns within the tables, and explored what they suggest for housing and financial inclusion. They also investigated other evidence to support these interpretations.

Limitations of our study

Credit unions are ethical organisations where the mutual ownership is shared among members. The scheme reported may not be transferred easily to commercial banks organised on different principles. LPCU already had good relationships with social landlords and the local government authority that provided the grant to support the scheme. LPCU had a balanced portfolio of members with different levels of savings, so staff existed to manage the homeless prevention loan scheme. These conditions contributed to the success of the scheme and their existence (or not) elsewhere will affect whether the scheme can be transferred to other contexts.

Table 1: Number of homeless prevention loans (2010 to 2020)